THE HOMONATOR

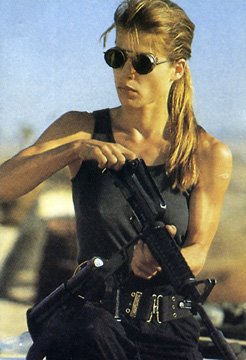

Years before Brandy Chastain ripped her soccer jersey off and paraded her guns at the Women's World Cup, Linda Hamilton was showing off her own assault muscles in "Terminator Two: Judgment Day."

I was raised Catholic, but before I saw Hamilton in T2 I had never actually used the words "Holy Mary, Mother of God!"

T2 is one of my favorite films, not just because Linda Hamilton is a sexy stud, and not just because it's one of the best action movies ever made, but because it's central point is that the best thing about people is not their scientific innovations or their impressive arsenals or even their Eiffel Towers or King Lears or Mona Lisas, but their ability to love.

Like, say you're an Einstein working on a Doomsday Machine to wipe out your country's enemy, who probably has a different skin color/religion from you, or, if your enemy is an alien species, gigantic ears and a bony forehead. Your research is hailed as a triumph of science and the pinnacle of human intellect, but then, as you are driving to your nuclear lab, you see a pretty girl picking flowers (or polishing her AK47) and you fall in love and forget about your Doomsday Device.

This is what Oscar Wilde meant by "The advantage of the emotions is that they lead us astray."

The tragedy of the Terminator, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, is that he has no emotions to lead him astray.

He is a machine. He has intellect, but no heart, like a Space Age Tin Man. But unlike the Tin Man, Arnold doesn't want a heart. A heart would interfere with his job, which is to save the human race.

When a teenager asks him whether he's afraid of dying, Arnold is baffled and says no: "I have to stay functional until my mission is complete."

Human emotion does not compute with the Terminator.

When the teenager sheds tears, he asks, "What's wrong with your eyes?"

When the same teen tells him, "You just can't go around killing people," he asks, "Why?" The teen: "What do you mean 'why'? Because you can't." The Terminator: "Why?" (And there are plenty of times in the movie where this seems like a perfectly valid question).

So the Terminator is tragic, but not a tragic hero.

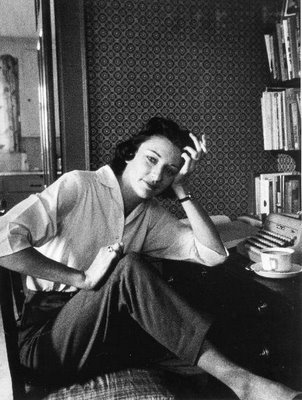

Hamilton, not Schwarzenegger, is the hero of T2. They both rid the world of bad guys, but Hamilton feels pain and anger and vengeance and sorrow while doing it. The genius of the movie is that she has trained herself — her body, her mind — to be more like a machine: focused on a mission, not led astray by emotion. She can drive a ballpoint pen through a dude's kneecap without batting an eyelash. But she ultimately fails in her mission to be a machine, and it's a failure that saves the day.

Her moral outrage is the film's fuel: "Fucking men like you built the hydrogen bomb. Men like you thought it up. You think you're so creative. You don't know what it's like to really create something; to create a life; to feel it growing inside you. All you know how to create is death..." (One of the many comic moments in the film is when her young son interrupts this monologue with "Mom! We need to be a little more constructive here, okay?")

So Hamilton the human is the hero, but Arnold the machine gets the choicest line: "The more contact I have with humans, the more I learn."

It doesn't have the zip of "Hasta la vista, baby!" and "I'll be back," the two most oft-quoted T2 lines, but it's the one that deserves to be remembered. Because it's the point of the film.

And it came back to me earlier this week during an e-mail conversation with Erin. I'll reprint my first e-mail to her and summarize the rest:

OK, I got to tell you this thing that happened at dinner last night. I was just trying not to think about it today (I might blog about it when I'm less upset). But I was asking my stepmom and dad about various relatives, how they're doing, etc., and my dad's little brother Danny came up in the conversation. He was diagnosed a long time ago with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. So I was asking questions about him, how he came to be diagnosed, etc., because I was a kid when all of that happened, and I would imagine that he did not get much support, knowing my family. So I was interested in his life and what it was like, etc., and I was asking some pretty pointed questions. Then my stepmom seemed very interested in the topic, and she said, "You know, I've always wondered, with Tim being Danny's twin and Tim going gay (her exact words), and Danny being manic-depressive if maybe something bad happened when Eileen was pregnant, if something was damaged, or a chromosome dropped or something." I just looked down at my plate. I couldn't look at her because I knew I would cry if I tried to say anything. So I didn't say anything. And my dad didn't say anything. And now I feel ashamed for letting her get away with that.

So that upset me, the idea that I'm damaged goods or mentally ill. And I told Erin that I was going to kill my stepmom. And she said, "You just can't go around killing people," and I said, "Why?" And she said: "What do you mean 'why'? Because you can't." And I said: "Why?"

No, wait. I'm misremembering that.

What Erin actually said was that my stepmom clearly wasn't thinking and was suffering some sort of vast disconnect between screwed-up notions of gayness put into her head by society and the gay person sitting right in front of her whom she shows all evidence of loving and accepting. I have heard Erin make this excuse for others before — people who operate on stereotypes in lieu of experience, people who have certain notions about gays or blacks or whatever simply because they have never been around gays or blacks or whatever. And she's totally right. These people are not evil; they're just inexperienced. Their CPU's have been poorly programmed. I shouldn't get mad or hurt or homicidal. I should just be more gay. So they don't forget whom they're dealing with.

In "T4: The Homonators," a script George and I are writing, the thematic line is going to be "The more contact I have with gay humans, the more I learn."

But probably the line everyone will remember will be "Hasta la vista, Mary!"