STILL AND ALWAYS

"I think during spring break I'll concentrate more on having fun instead of trying to figure everything out." — Erin Gough, 12, in her diary

Here's something damn bleak.

(Bleak as in stark. As in grimly blunt. As in sort of beautiful.)

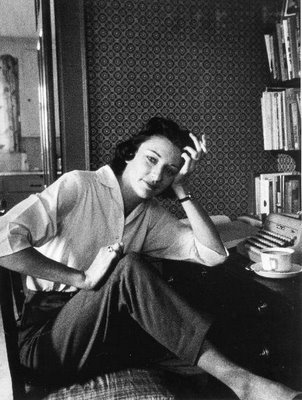

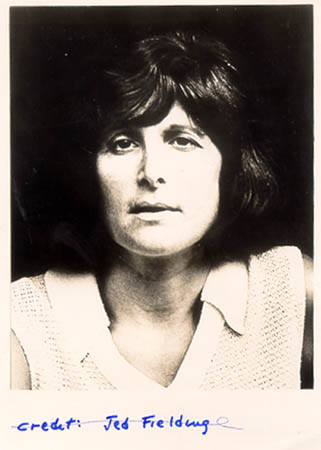

Maxine Kumin, one of my favorite poets, has a poem in the current New Yorker about Anne Sexton, another of my favorite poets, who killed herself on Oct. 4, 1974.

Kumin and Sexton were best friends.

In the poem, called "Revisionist Dream," Kumin dreams that Sexton is still alive, that she is taking piano lessons and translating Anna Akhmatova and making coq au vin.

The dream, of course, "blew up at dawn." Sexton isn't alive. She isn't almost 80. She gassed herself in her garage at age 43, just after lunch.

After 32 years of the fact, deep down the mind still rejects it.

In the dream, ""It was a mild day in October, we sat outside/over sandwiches. She said she had begun/to practice yoga."

In the dream, Sexton "hugged me, went home, cranked the garage doors open,/scuffed through the garish leaves, orange and red,/that brought on grief."

In real life, Sexton drove off after lunch, said something out her car window that Kumin didn't hear, then cranked open the garage doors, and closed them, and left her car running.

To tell the truth, this poem doesn't resonate with me much as a poem — not like the poem Kumin wrote about wearing Sexton's sweater after she died, not like her startling "woodchuck" poem. I don't see the poetry in this new one exactly, but then Maxine Kumin is the one with the Pulitzer Prize, not me. What resonates most with me is its quality as a human document, a testament to the doggedness of memory, the impossible delicacy of our physical connection to each other and the almost unbearable solidity of our mental one, and as a testament to the significant, mysterious moment. Like the moment of Mrs. Dalloway kissing Sally. Of Lot's wife looking back at Sodom ("who suffered death because she chose to turn"). Of Anne Sexton's last — unheard — words.

I read a biography of Sexton years ago. Here's what I remember:

She was a housewife.

She suffered chronic depression. Her psychologist recommended poetry as therapy.

She took a poetry class. And met Maxine Kumin there.

They became friends. They critiqued each other's work. They raised each other's kids. They drank vodka and read poems in a swimming pool that Sexton — scandalously — bought with grant money.

Often they concentrated more on having fun instead of trying to figure everything out.

They each won a Pulitzer Prize.

They had affairs.

Sexton wrote to her baffled, jealous husband (I'll always remember this): "No, you are not the man of my dreams; you are my life." (Christ, I'd settle for that.)

And I saw Maxine Kumin read her poetry in Kansas City right after I read the Sexton biography, maybe a dozen years ago. I had Kumin sign my copy of her poems. It was the first time I asked anyone for an autograph. And I didn't want her autograph; I just wanted to be in her space for a second. She seemed old and frail, yet tough, exactly like someone should who had spent decades in rural New England raising horses and writing verse. Like someone who lived close to the earth. There were references to Sexton in some of the poems she read that night. I wanted to ask her what she felt, if anything, speaking those allusions to strangers. Performing them for strangers, over and over. It must have had, I see now, no resemblance to the unbidden dream. But that's not a question you could possibly ask someone. Because the answer, even if she felt like giving one, is a lost ingredient, just like in Sexton's poem.

The Lost Ingredient

Almost yesterday, those gentle ladies stole

to their baths in Atlantic City, for the lost

rites of the first sea of the first salt

running from a faucet. I have heard they sat

for hours in briny tubs, patting hotel towels

sweetly over shivered skin, smelling the stale

harbor of a lost ocean, praying at last

for impossible loves, or new skin, or still

another child. And since this was the style,

I don't suppose they knew what they had lost.

Almost yesterday, pushing West, I lost

ten Utah driving minutes, stopped to steal

past postcard vendors, crossed the hot slit

of macadam to touch the marvelous loosed

bobbing of The Salt Lake, to honor and assault

it in its proof, to wash away some slight

need for Maine's coast. Later the funny salt

itched in my pores and stung like bees or sleet.

I rinsed it off on Reno and hurried to steal

a better proof at tables where I always lost.

Today is made of yesterday, each time I steal

toward rites I do not know, waiting for the lost

ingredient, as if salt or money or even lust

would keep us calm and prove us whole at last.

9 Comments:

In a way, I'm in this city with this job because I've still been searching for my "lost ingredient." I realized this a few months ago, you might remember me hitting rock bottom; I ended up losing something else.

Since then I have resolved to have more fun rather than try to figure things out. That's why I'll take any excuse to make a visit to Lawrence.

Lovely post, kc.

It really is great. I don't know what else to say.

(thanks)

Get your ass up here, George!

I'm workin' on it!

One of my favorite Fitzgerald lines is this:

“When we are in our thirties we want friends. In our forties we know that they won’t save us anymore than love did.”

Seems that there is an unending search for a seasoning for the unpalatable bits.

One of my favorite Fitzgerald lines is this:

“When we are in our thirties we want friends. In our forties we know that they won’t save us anymore

Hey, you have a great blog here! I'm definitely going to bookmark you!

I have a vinyl pet toy site.

Come and check it out if you get time :-)

Greetings.

I have always wondered about your love affairs with dead writers. Scared to put my finger on it or else make you feel bad for something that is oddly wonderful. Also, this is one of my favorite poems of all time, as are most of the poems you sent me when I was 19.

Post a Comment

<< Home